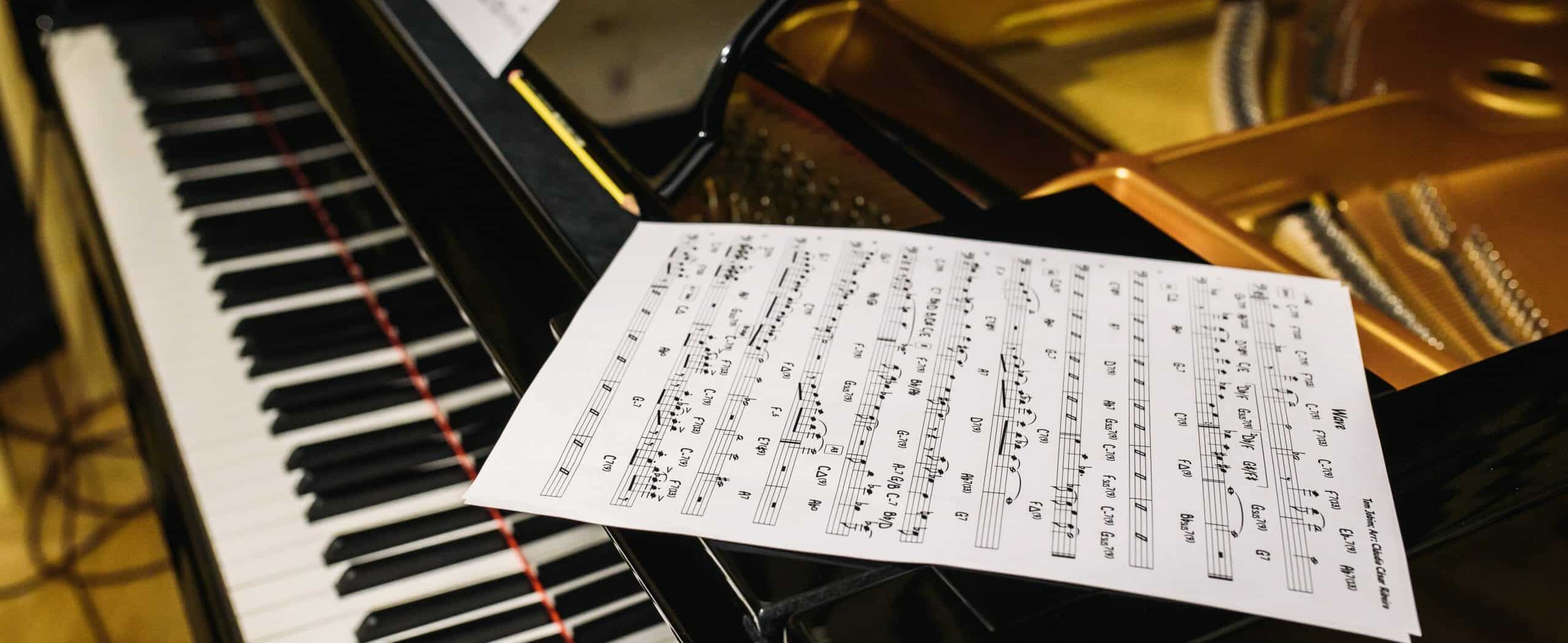

One of the most neglected aspects of learning the piano nowadays is sight reading. One of the most useful, necessary skills when playing a musical instrument is sadly sidelined by most students and teachers because “it’s too hard,” or “it’s too much work to teach it properly.”

Unfortunately, this has led to most pianists being unable to sight read properly. This problem is not endemic to beginner and intermediate students; I’d wager that if you go into most conservatoires nowadays, you will find students struggling to sight read, even at the postgraduate and doctoral levels.

So what can you do if you are struggling and want to improve your sight reading? Fortunately, even if you struggle to read more than one bar of music without hesitation, there are a series of actionable tips and insights you can take in order to improve.

What is Sight Reading?

Firstly, let’s get into what sight reading is and what it is not. Sight reading is:

“The act of playing a piece of music at first sight; without ever having seen or practiced it before.”

Let’s look at exactly what this means.

If you are presented with a piece of music that you have never, ever seen before, and you are asked to play it there and then, then you would be sight-reading. However, once you have played through that piece of music, you are UNABLE to ever sight read it again. Anything after that is simply called “reading.”

Sight reading well involves the culmination and combination of many different skills. The ability to identify notes and chords, to be able to correctly identify time signatures and key signatures, to be able to look at the composer’s tempo and articulation markings and generate a convincing performance.

What sight reading is not is playing a piece perfectly without ever having seen it before.

What other skills are involved in sight reading?

As we discussed, sight reading does not mean playing a piece absolutely 100% perfectly at first sight. Very few, if any musicians can do this. Even though there are elements of being able to interpret a piece accurately based on what’s on the page without having seen it before, there are much more nuanced elements that come into play when a good sight reader sight reads a piece.

The one absolutely key aspect of good sight reading is being able to maintain a consistent tempo.

It is not:

- Playing all the right notes.

- Following all the composer’s directions.

- Reading the key signature right.

- Reading the time signature right.

- Making your performance as expressive as humanly possible.

These things are what PRACTICE is for.

This may be difficult to understand for some people not familiar with these concepts, but think of it in this way. Many good sight readers are accompanists. They may accompany a singer, an instrumentalist, or they may even be part of an orchestra.

If you are playing with a singer, what do you think is most important for them? The fact that you can keep a reliable and consistent tempo or that you played a few wrong notes or some of your rhythms were a little inaccurate?

Or, do you think they’d prefer every note and rhythm was correct and you stopped every few bars to go back to correct yourself? If you keep stopping and starting and correcting wrong notes you are going to annoy the hell out of our audience and your singer because they will keep getting lost.

What’s far more important is keeping up with them, at a consistent tempo, to the point where you’re able to support their performance successfully. A few wrong notes, misread rhythms, etc aren’t going to bother them.

There’s a limit to this, however; if your notes are all over the place, even if your rhythm is correct, it won’t sound very good. You need to have a certain degree of note-reading accuracy, but as we mentioned, this is very flexible and nobody will really care if you play wrong notes as long as you can cover them well.

Why would I want to sight read?

We’ve gone through what sight reading is and what it isn’t. Now let’s look at why you might want to sight read. I’ve used an analogy of playing with a singer, but what if you don’t have a singer or an instrumentalist to play with? Surely then sight reading doesn’t matter?

Not so.

I will preface this section by saying that the ability to play with or accompany someone else is a really valuable skill, and not being able to do it will rob you of some great musical experiences. In my opinion, this alone is worth being able to sight read. The joy of sitting down to play with someone else you’ve never played with before without worrying about an exam or an audience is one of the best things about being able to play an instrument.

However, if you are just a solo player and have no interest in playing with anyone else, sight reading is still exceptionally useful for you, simply because it allows you to learn new pieces much, much quicker. Most pianist’s problem when learning new music isn’t their technical ability to play the notes; it’s that they can’t read and learn the notes quickly enough.

If you can sight read well, you don’t really have to worry too much about learning the notes; you can get into actually learning the music and learning how to play it well and expressively much more quickly, without having to spend hours and hours working out a chord or a scale pattern. You instinctively know where to place your fingers, and in my experience, that kind of rapidity of learning is invaluable.

Why sight reading is such a problem nowadays

As I mentioned before, people nowadays struggle to sight read. This is something that was taught pretty religiously in the past, especially in terms of the piano. Piano pedagogy has changed over the last 100 years or so, to the point now where actually learning the piano is very different to learning another instrument.

Let’s use the violin as an example. If you’ve ever listened to a violinist practice, you’ll hear that they spend very little time actually practicing pieces. They almost exclusively practice exercises and studies. Why is this? It’s because there’s much more of an impetus to be able to sight read well, and be able to put pieces together quickly.

Think about it. If you play in an orchestra, you’ll likely be given sheet music maybe one week or two weeks before a performance. Do you really have the time to learn your part in two weeks? Probably not. This is why the emphasis is on technical proficiency (hence why violinists practice mostly exercises) and on being able to read and learn quickly. There’s almost no value placed on being able to memorise long works, because the daily working life of a professional violinist or violin student doesn’t call for it.

Now imagine learning the piano today. Pianists are almost completely the opposite; we spend large portions of time practicing pieces, rather than exercises. Given that we rarely play in orchestras and rarely have the impetus (or the need) to learn pieces very quickly to play with others, we don’t develop that sight reading ability.

If you learned piano 100 years ago, you’d have most likely learned like a string player. You would have had the technical ability and the reading ability to learn most pieces very quickly and wouldn’t really need to spend hours and hours practicing them in order to just play them.

Whether this is right or wrong is not for me to say; it’s just how it is. However, it means that pianists need to specifically work hard on their sight reading, in a way that is just part and parcel of the learning experience of a string player or a wind player.

How to improve your sight reading

Enough philosophy. Let’s get into what you came here for; actionable tips on how to improve your sight reading. Firstly, we’re going to go through some basic steps to get you started, and as you improve you can incorporate my “key principles of sight reading” into your practice.

1. Find your level

As obvious as this is, some students fall at this hurdle because they pick music that’s just way too hard for them to sight read. If you are new to sight reading, or struggle at it, trying to pick the pieces you would normally play and sight reading them is going to doom you to failure.

For example, if you’re at Grade 5 level, you’re highly unlikely to be able to sight read other Grade 5 pieces (or if you could, you probably wouldn’t be reading this article about how to improve your sight reading.) You should go through the grades, find sheet music online (or anywhere else you can get it) and try to sight read as many pieces as you can until you have determined your level.

If your level is a Grade 1 piece, then great. That’s your ability and that’s where you start. But it’s hugely important to determine this before buying or borrowing loads of music to sight read; if the music is just too hard for you, you will get disheartened and discouraged.

2. Grab as much music as you can

Once you’ve determined your level, you need to have a continuous supply of new music. As we mentioned before, “sight reading” is not simply “reading” and in order for you to get better at sight reading you need to have a constant feed of fresh, new music you’ve never seen before.

This can be difficult (and expensive) if you don’t have a huge music collection already. However, if you have a university near you with a music department, see if you can become a member of their library. There, they will have all the music you will ever be able to read in your lifetime, and you’ll be able to check out as much as you’d like. As soon as you’ve read through, return and check something else out. You might also want to look at beginner piano books for some inspiration.

Alternatively if you can’t do this, get yourself an iPad and download PDFs from IMSLP. There’s as much free music as you can shake a stick at on there; you will never run out of music to read.

3. Read, read, and read some more

Of course, all this music is useless if you don’t practice it. Sit at your piano for 20 minutes a day and just read through it. Don’t repeat, don’t go back; just treat it as if it were a book with words in it rather than music. Start at the beginning, and go on until the end. When you’ve finished, move onto the next book.

It’s really important that you go against your instinct to stop, go back, practice a bar or two, check the voicing of a chord, check your notes, etc etc. It doesn’t matter. You either get it right the first time or you move on. Never, ever stop to correct mistakes.

The 7 Key Principles of Sight Reading Practice

To finish off this article, I’ve come up with seven different principles that you need to live by when practicing your sight reading. These are super-important, and if you follow them to the letter your sight reading will improve quicker than you might expect.

Don’t stop

I’ve mentioned this several times but it’s so important that I’ll keep saying it.

Never, ever go back to correct your mistakes.

Do not stop playing until you have reached the end of the piece.

If you need to imagine that there’s someone holding a gun to your head who will pull the trigger if you stop playing, then so be it. That’s how important it is that you keep playing. Do not ever stop to correct your mistakes. In concert, you have one chance to play the correct note, and if you do not, then you keep moving; the moment has passed. Treat your practice the same.

Don’t worry about wrong notes

As a continuation of the previous point, you should also not worry if you play a wrong note. A wrong note is insignificant. I feel like some students think that if they do not somehow go back to correct their wrong notes, it will negatively impact their ability to read music. This is not true. You know it was wrong; that is enough.

I’ll say it again; if you play a wrong note it does not matter. The only thing that matters is that you keep playing.

Don’t read the same piece twice

You can only ever sight read a piece once. Once you’ve sight read it once (even partially) you can never sight read it again; you can only read it. At this point muscle memory starts to come into play, and you are no longer practicing your sight reading - you are learning a piece.

Once you’ve read a piece, move on to the next one. Once you’ve finished the book those pieces are in, go and buy or borrow another book. Once you’ve read the piece, it’s over; it has already contributed everything it will ever contribute to your sight reading. Find something else to read.

Think of your mind as a sponge, where you need to absorb as much music as humanly possible in order to improve your sight reading. You won’t gain anything from re-reading; you have to read new pieces if you are going to improve your sight reading.

Find a variety of music

Sticking with the same type of music is OK, but you won’t learn nearly as quickly or as much as if you vary the music you read. Keep your brain guessing; the more your brain has to work to understand different styles the quicker you will improve.

Maybe check a book of Strauss Lieder out of the library. Once you’ve finished that, read through some Bach chorales or some church hymns. After that, read through some Mozart. After that, pick some pop songs, or some jazz. Always mix things up.

Read music you don’t like

This is an interesting one; you should read a wide variety of music, but don’t just pick music that you like. Pick anything; even the stuff you don’t like. This ensures your sight reading ability is as rounded and as all-encompassing as possible.

If you’re a rehearsal pianist and you get presented with a piece of music you hate, are you going to refuse to read it? Probably not. Practice for this and similar situations; it’ll keep you sharp and on your toes.

Start as slow as you need to

When you start practicing sight reading, there’s a temptation to race ahead and immediately play at tempo. Don’t do this. It doesn’t matter when you’re practicing (although it does matter in performance.)

Keep things at a balanced tempo, where it’s not so slow that you’re in your comfort zone, but it’s not so fast that you can’t cope. Keep it at a challenging tempo where you’re forced to work hard, but it’s not so challenging that your playing falls apart.

Ensure you are reading ahead

This is really critical. You will never sight read well unless you get used to reading ahead. If you don’t read ahead, you don’t know what’s coming. Ensure that you’re always looking at least one or two bars ahead so you can prepare yourself for what’s about to happen in the music.

Thank you for this great insight. This is encouraging.

Thank you so much. Your article on “Sight Reading” has helped me immensely in understanding the subject

Thank you for the article. I didn’t learn to play 100 years ago, but my teachers did. They thought a portion of my regular practice should be sight reading. Now that I’m teaching and talking to my students about it, I thought I should incorporate it into my practice intentionally. Humbling.

What a wonderful piece of information! I’m 74 years old and I’m teaching myself to read notes, but coming from an engineering background, I had always strived for perfection, no matter how many tries it takes to get it right. Not anymore! I fully understand the principle of being fluid and to keep going with the music instead of stopping and trying to get it right. I can read a full octave of notes with both hands at a time, but it’s almost going to be like starting over with this new discipline. I’m glad I found this article early on and not a year or two down the road where it would have been much more difficult to correct.

Thank you,

Carlos

Thank you so much I really appreciate everything that you said and teaching my grandchildren to sight read this is going to be very helpful again keep giving lessons you’re very much appreciated. Charmaine

I love your directness…no fussy frills, just straight talk, answering all anticipated questions and excuses in a compassionate and clear way.

Thanks Jack for the brilliant article, short and concise.

One question remains. What about looking down on the hands? Is it ok to take a glimpse while sight reading? Or completely forbidden as it interrupts the reading process?

Looking forward for an answer.

I am just beginning to learn to read music and play the piano. My lesson this week was on sight reading. Whoa, scared me a bit! After reading your fabulous article, I can see the definite benefits of learning to sight reading. Thank you!